Pedro II of Brazil

| Pedro II | |

|---|---|

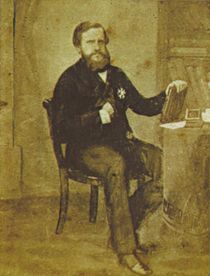

| Pedro II wearing a Marshal of the Army's court dress around age 25, c. 1851. | |

|

|

|

| Reign | 7 April 1831 – 15 November 1889 (58 years, 222 days) |

| Coronation | 18 July 1841 |

| Predecessor | Pedro I |

|

|

|

| Pretendence | 15 November 1889 – 5 December 1891 (2 years, 20 days) |

| Successor | Isabel, Princess Imperial |

| Spouse | Teresa of the Two Sicilies |

| Issue | |

| Afonso, Prince Imperial Isabel, Princess Imperial Leopoldina, Princess of Saxe-Coburg-Kohary Pedro, Prince Imperial |

|

| Father | Pedro I of Brazil |

| Mother | Maria Leopoldina of Austria |

| Born | December 2, 1825 Palace of São Cristóvão, Rio de Janeiro |

| Died | December 5, 1891 (aged 66) Paris, France |

| Signature | |

Pedro II (Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈpedɾu]; English: Peter II; 2 December 1825 – 5 December 1891), nicknamed "the Magnanimous"[1][2] was the second and last ruler of the Empire of Brazil, reigning for over 58 years.[a] His name in full was Pedro de Alcântara João Carlos Leopoldo Salvador Bibiano Francisco Xavier de Paula Leocádio Miguel Gabriel Rafael Gonzaga (English: Peter of Alcantara John Charles Leopold Saviour Vivian Francis Xavier of Paula Leocadio Michael Gabriel Raphael Gonzaga).[1][3][4][5] He was born in Rio de Janeiro, the seventh child of Emperor Dom Pedro I of Brazil and Empress Maria Leopoldina. He was a member of the Brazilian branch of the House of Braganza and was referred to using the honorific "Dom".[6]

His father's abrupt abdication and flight to Europe left a 5-year-old Pedro as Emperor and led to a grim and lonely childhood and adolescence. Obliged to spend his time in studying in preparation for rule, he knew only brief moments of happiness and encountered few friends of his age. His experiences with court intrigues and political disputes during this period greatly affected his later character. Pedro II grew into a man with a strong sense of duty and devotion toward his country and his people. He also increasingly resented his role as monarch.

Inheriting an empire on the verge of disintegration, Pedro II turned Portuguese-speaking Brazil into an emerging power in the international arena. The nation grew to be distinguished from its Hispanic neighbors on account of its political stability, zealously-guarded freedom of speech, respect for civil rights, vibrant economic growth and especially for its form of government: a functional, representative parliamentary monarchy. Under his rule Brazil also achieved victory in three international conflicts (the Platine War, the Uruguayan War and the War of the Triple Alliance), as well as prevailing in several other international disputes and internal disruptions. He steadfastly pushed through the abolition of slavery, despite opposition from powerful political and economic interests. The Emperor, a savant in his own right, established a reputation as a vigorous sponsor of learning, culture and the sciences. He won the respect and admiration of scholars such as Charles Darwin, Victor Hugo and Friedrich Nietzsche. He was a friend to Richard Wagner, Louis Pasteur and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, among others.

Although there was no desire for a change in the form of government among most Brazilians, the Emperor was overthrown in a sudden coup d'état which had almost no support outside a clique of military leaders who aspired for a form of republic headed by a dictator. Pedro II had become weary of emperorship and despaired over the monarchy's future prospects, despite its overwhelming popular support. He allowed no intervention to prevent his ouster and did not support any attempt to restore the monarchy afterwards. His last two years of life were spent in exile in Europe living alone on very little money.

Pedro II represents a rare, perhaps unique, instance of a successful monarch who was overthrown even though greatly beloved by his people and at the pinnacle of his popularity. Most of his accomplishments were soon brought to naught as Brazil slipped into a long period of anarchy, dictatorship and economic crises. The same men who had exiled him soon began to see in him a model for the Brazilian republic. A few decades after his death his reputation was restored and his remains were returned to Brazil as those of a national hero.[7] This reputation has lasted to the present day. Historians have regarded the Emperor in an extremely positive light, and he is usually ranked as the greatest Brazilian.[1][8][9]

Contents |

Early life

Birth

Pedro was born at 2:30 a.m. on 2 December 1825 in the Palace of São Cristóvão, located in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.[10][11][12] His name was a homage to St. Peter of Alcantara.[13][14] Through his father, Emperor Pedro I, he was a member of the Brazilian branch of the House of Braganza. He was the grandson of Portuguese King João VI and nephew of Miguel I.[15][16] His mother was the Archduchess Maria Leopoldina of Austria, daughter of Franz II, last Holy Roman Emperor. Through his mother he was a nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte and first cousin of Emperors Napoleon II of France, Franz Joseph I of Austria and Maximilian I of Mexico.[17][16][18][19]

The only legitimate male child of Pedro I to survive infancy, he was officially recognized as heir to the Brazilian throne with the title Prince Imperial on 6 August 1826.[3][20] Empress Leopoldina died on 11 December 1826, a few days following the stillbirth of a male child,[21][22] when Pedro was one year old.[23][19][24] Pedro would have no memory of his mother apart from what he was later told about her.[23][25] Of his father, "he retained no strong images of him" in adulthood.[26]

His father was married two and a half years later to Amélie of Leuchtenberg. Prince Pedro spent little time with his stepmother, who ultimately abandoned the country two years later. Even so, they had an affectionate relationship[22][27][28] and kept in contact until her death in 1873.[29] Emperor Pedro I abdicated on 7 April 1831, after a long conflict with the liberals. He and Amélie immediately departed for Europe to restore his daughter to the Portuguese throne, which had been usurped by his brother Miguel I.[30][31] Left behind, Prince Imperial Pedro became Dom Pedro II, Constitutional Emperor and Perpetual Defender of Brazil.[12]

Education

Upon leaving the country, Emperor Pedro I selected three people to take charge of his son and remaining daughters. The first was José Bonifácio, his friend and an influential leader during Brazilian independence, who was nominated as guardian.[32][33] The second was Mariana de Verna, who had occupied the position of aia (supervisor) from the birth of Pedro II.[34] Pedro II called her "Dadama" as he did not pronounce the word "dame" correctly as a child.[20] However, he would continue calling her in this way into adulthood out of affection and as his surrogate mother.[3][10][23][20][35] The third person was Rafael, an Afro-Brazilian veteran of the Argentina-Brazil War[34][36]. Rafael was an employee in the Palace of São Cristóvão (Pedro II's primary residence from infancy)[37] whom Pedro I deeply trusted and asked to look after his son—a charge which he carried out during the rest of his life.[3][36]

Bonifácio was dismissed from his position in December 1833 and replaced by another guardian.[38][39][40] Pedro II passed the entire day studying[41] with only two hours reserved for amusements.[42] He would wake up at 6.30 a.m. and begin studies at seven, continuing until 10 p.m., after which he would go to bed.[43] Great care was taken to guide him away from his father's example in matters related to education, character and personality.[38][44] His passion for reading allowed him to assimilate any information.[45] Pedro II was no genius[24] but he was intelligent[46] and had a facility for accumulating knowledge.[47]

The Emperor experienced an unhappy and solitary childhood.[3][48] The sudden loss of his parents "was to haunt Pedro II throughout his life".[49] He had few friends of his age,[34][43][50] and even contact with his sisters was limited.[41][50][38] The environment in which he was raised turned him into a shy and needy person[51][52] who saw in "books another world where he could isolate and protect himself."[53][54]

An early coronation

The elevation of Pedro II to the Imperial throne in 1831 led to a period of crisis, the most troublesome in Brazil's history.[55] A regency had been created to rule on his behalf until he reached the age of majority.[30] Disputes between political factions led to several rebellions and resulted in an unstable, almost anarchical, situation under the regents.[56]

The possibility of lowering the young emperor's age of majority, instead of waiting until he turned 18 on 2 December 1843, had been floated since 1835.[57][58][59] The idea had received support from both main political parties.[60][58] It was thought that those assisting him in taking the reins of government would be in a position to manipulate the inexperienced youth.[61] Those politicians who had assumed power during the 1830s had by now also become familiar with the pitfalls of governing. "By 1840 they had lost all faith in their ability to rule the country on their own. They accepted Pedro II as an authority figure whose presence was indispensable for the country's survival."[62] The Brazilian people also supported lowering the age of majority,[63] as they considered Pedro II "the living symbol of the unity of the fatherland" and this position "gave him, in the eyes of public opinion, a higher authority than that of any regent."[64]

Those advocating immediately raising Pedro II to majority passed a motion requesting the Emperor to assume full powers.[65] A delegation was sent to the Palace of São Cristóvão to ask if Pedro II would accept or reject an early declaration of his majority.[66][67][68][65] He shyly answered "Yes" when asked if he desired the age of majority to be lowered, and "Now" when asked if he would prefer that it come into effect at that moment or if he preferred to await his birthday in December.[69][70] On the following day, 23 July 1840, the Assembléia Geral (the National Assembly) formally declared the 14-year-old Pedro II of age.[71][72] There, in the afternoon, the young emperor took the oath of office.[73][74] He was acclaimed, crowned and consecrated on 18 July 1841.[75][76]

Consolidation

Marriage

Removal of the factious regency stabilized the government. With a legitimate monarch on the throne, authority was vested in a single, clear voice.[77] Pedro II perceived his role as that of an arbiter, keeping personal views from hindering his duty to untangle partisan political disputes.[77] The young Emperor was diligent in his new role, making daily personal inspections and visits to government branches. His subjects were impressed by his seeming self-confidence,[77] though his shyness and lack of social grace were considered flaws. "Since he rarely volunteered more than a word or two, maintaining a direct conversation with him was next to impossible."[78] His taciturn nature manifested a suspicion of close relationships that traced to incidents of abandonment, intrigue and betrayal experienced during his childhood.[79]

Behind the scenes, a group which became known as the "Courtier Faction" established influence over the young Emperor. These courtiers were high ranking palace servants and notable politicians. Some were very close to the Emperor.[80] Pedro II was deftly used by the courtiers to eliminate their foes (actual or suspected) by obtaining the dismissal of rivals. Access to his person by rival politicians and the flow of information he received was strictly controlled. A continuous round of meetings, study, personal appearances and government business, used as distractions, kept the Emperor occupied, effectively isolating and keeping him unaware of being exploited.[81]

Concerned over the Emperor's taciturnity and immaturity, the courtiers believed marriage would improve his behavior and character.[82] The government of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies offered the hand of Princess Teresa Cristina.[83][84][85][86] A portrait of Teresa Cristina was sent by the Kingdom to Pedro II, depicting a beautiful young woman and prompting him to accept the match.[83][87][88][89] The new Brazilian Empress arrived on 3 September 1843.[83][90][91][92] Upon seeing her in person, he was clearly disappointed.[82][93][94][95][96] The picture he had been sent was clearly an idealization; the real Teresa Cristina was short, a bit overweight, walked with a pronounced limp and though not ugly, neither was she pretty.[82][93][95][96] He did little to hide his disillusionment. "According to one report he turned his back on his bride, and another stated that he was so overcome that he had to sit down. […] He may have done both these things."[82] That evening, Pedro II wept and complained to Mariana de Verna, "They have deceived me, Dadama!"[82][94][96] It took several hours to convince him that duty demanded that he proceed.[82][94][96] The wedding celebration occurred on the following day, 4 September.[97][98][99]

Imperial authority established

By 1846 Pedro II had matured both physically and in character. He was no longer an insecure 14-year-old "willing to pay heed to gossip, give credence to alleged plots against himself, and let his conduct be manipulated by those surrounding him".[100] At 1.90 meters (6 ft 2.8 in) tall[101][102] with blue eyes and blond hair,[82][101][68] he had developed into a handsome man.[45][103][82] With growth, his weaknesses faded and his strengths of character came to the fore. He learned to be not only impartial and diligent, but also courteous, patient and personable. As he began to fully exercise authority, his new social skills and diligence in government contributed greatly to his effectiveness and public image.[100] "He kept his emotions under iron discipline. He was never rude and never lost his temper. He was exceptionally discreet in words and cautious in action."[104]

The end of 1845 through the beginning of 1846 found the Emperor making a tour of Brazil's southern provinces, traveling through Santa Catarina, São Paulo (of which Paraná was a part at this time) and Rio Grande do Sul. He was buoyed by the warm and enthusiastic responses he received.[105] This success encouraged him, for the first time in his life, to act confidently on his own initiative and insights.[106] Most importantly, this period saw the end of the Courtier Faction. Pedro II successfully engineered the end of the courtiers' influence by removing them from his inner circle while avoiding any public disruption.[107]

Pedro II was faced by three crises during the decade between 1848 and 1852.[104] The first test came in confronting the trade in illegally imported slaves. This had been banned in 1826 as part of a treaty with Britain.[108] The traffic continued unabated, however, and the British government's passage of the Aberdeen Act of 1845 authorized British warships to board Brazilian shipping and seize any found involved in the slave trade.[109] While Brazil grappled with this problem, the Praieira revolt erupted on 6 November 1848. This was a conflict between local political factions within Pernambuco province, and was suppressed by March 1849. A bill was promulgated on 4 September 1850 which gave government broad authority to combat the illegal slave traffic. With this new tool, Brazil moved to eliminate importation of slaves. By 1852 this first crisis was over, with Britain accepting that the trade had been suppressed.[110]

The third crisis entailed a conflict with the Argentine Confederation regarding ascendancy over territories adjacent to the Río de la Plata and free navigation of that waterway.[111] Since the 1830s, the Argentine dictator Don Juan Manuel de Rosas had supported rebellions within Uruguay and Brazil. It was only in 1850 that Brazil was able to address the menace presented by Rosas.[111] An alliance was forged between Brazil, Uruguay and disaffected Argentines.[111] This led to the Platine War and the subsequent overthrow of the Argentine ruler in February 1852.[112][113] A "considerable portion of the credit must be [...] assigned to the emperor, whose cool head, tenacity of purpose, and sense of what was feasible proved indispensable."[104]

The Empire's successful navigation of these crises considerably enhanced the nation's stability and prestige, and it emerged as a hemispheric power.[114] Internationally, Brazil began to be looked upon by Europeans as embodying familiar liberal ideals such as freedom of the press and constitutional respect for civil liberties. Its representative parliamentary monarchy also stood in contrast to the mix of dictatorships and instability endemic in the other nations of South America during this period.[b][115][116][117]

Growth

Pedro II and politics

At the beginning of the 1850s, Brazil was enjoying internal stability and economic prosperity.[118][119] The nation was being interconnected through railroad, electric telegraph and steamship lines, uniting it into a single entity.[118] The general opinion, both at home and abroad, was that these accomplishments had been possible for two reasons: "its governance as a monarchy and the character of Pedro II".[118]

Pedro II was neither a British-style figurehead nor an autocrat in the manner of Russian czars. The Emperor exercised power through cooperation with elected politicians, economic interests, and popular support.[120] This interdependence and interaction did much to influence the direction of Pedro II's reign.[121] The Emperor's great successes were achieved due largely to the non-confrontational and cooperative manner with which he approached both issues and the political figures with which he had to deal. He was remarkably tolerant, seldom taking offense at criticism, opposition, or even incompetence.[122] He was diligent in appointing only highly-qualified candidates to positions in the government, and sought to curb corruption.[123] He did not have the constitutional authority to force acceptance of his initiatives without support, and his collaborative approach towards governing kept the nation progressing and enabled the political system to successfully function.[124]

The uncertainty of his childhood and exploitation at the hands of others during his youth made the Emperor determined to maintain control over his own destiny. And to achieve self-determination required that he acquire and maintain sufficient power.[125] He used his active and essential participation in directing the course of government as a means of influence. And though his direction became indispensable, it never devolved into "one-man rule."[126] The Emperor respected the prerogatives of the legislature, even when they resisted, delayed, or thwarted his goals and appointments.[127]

The Brazilian national political system resembled those in other parliamentary nations. The Emperor, as head of state, would ask the leader of either the Conservative or Liberal Party to form a cabinet. The other party formed the opposition in the legislature, a counterweight and check on the party in power. If support for the party in power diminished greatly, or if the cabinet resigned, the Emperor could call on others from either party to form a new government. "In his handling of the two parties, he needed to maintain a reputation for impartiality, work in accord with the popular mood, and avoid any flagrant imposition of his will on the political scene."[128]

The active presence of Pedro II on the political scene was an important part of the government's structure, which also included the cabinet, the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate (the latter two formed the National Assembly, or Parliament). Most politicians appreciated and supported the Emperor's role. Many had lived through the regency period, when the lack of an emperor who could stand above petty and special interests led to years of strife between political factions. "Experienced had taught" them "to regard the emperor as indispensable to Brazil's continued peace and prosperity."[129]

Domestic life

The marriage between Pedro II and D. Teresa Cristina started off badly. With maturity, patience, and their first child, Afonso, their relationship improved.[112][130] Later Teresa gave birth to more children: Isabel, in 1846; Leopoldina, in 1847; and lastly, Pedro, in 1848.[131][96][132][133] However, both boys died when very young, and the Emperor was devastated.[134][96][132] Beyond suffering as a father, his view of the Empire's future changed completely. Despite his affection for his daughters, he did not believe that Princess Isabel, though his heir, would have any chance of prospering on the throne. "To be viable his successor had to be a man."[135] He increasingly saw the Imperial system as being tied so inextricably to himself, that it would not survive him.[136] Isabel and her sister received exceptional educations,[137] though they were given no preparation for governing the nation. Pedro II excluded Isabel from participation in government business and decisions.[138]

Sometime around 1850, Pedro II began having discreet affairs with other women.[139] The most famous of these was Luísa Margarida Portugal de Barros, Countess of Barral, who had become governess to the emperor's daughters in August 1856.[140][141][132] Throughout his life, the Emperor held onto a hope of finding a soulmate, something he felt cheated of[142] due the necessity of a marriage of state to a woman for whom he never felt passion.[143] This is but one instance illustrating the Emperor's dual identity: who on one hand was "Dom Pedro II" who assiduously carried out his duty in the role of Emperor which destiny had assigned to him, and who on the other hand was "Pedro de Alcântara" who considered the Imperial office an unrewarding burden and who was happier in the worlds of literature and science.[144] Pedro II was what would today be termed a workaholic, and his routine was demanding. He usually woke up at 7 am and did not sleep before 2 in the morning. His entire day was devoted to the affairs of state and the meager free time available was spent reading and studying.[145] The Emperor went about his daily routine dressed in a simple black tail coat, trousers, and cravat. For special occasions he would wear court dress, and he only appeared in full regalia (that is with crown, mantle, scepter, etc.) twice each year at the opening and closing of the National Assembly.[146][147]

Pedro II held politicians and government officials to the strict standards which he exemplified.[148] The Emperor demanded politicians work at least an eight hour day and adopted a strict policy for the selection of civil servants based on morality and merit.[149] To set the standard, he lived simply. Balls and assemblies of the Court ceased after 1852.[144][150] He also refused to request or allow the amount of his civil list (Rs 800:000$000 per year, about then-U.S. $405,000 or £90,000[151]) to be raised from 1840, when it represented 3% of the government expenditures, until 1889, when it had fallen to 0.5%.[152][153] He refused luxury,[154][155][156] once explaining: "I believe that useless expenditure is robbing the Nation".[157]

Patron of arts and sciences

"I was born to devote myself to culture and sciences", the Emperor remarked in his private journal during 1862.[159][160] He had always been eager to learn and found in books a refuge from the demands of his position.[161][162] His ability to recall passages which he had read in the past was both notable and noted.[163][164] Subjects which interested Pedro II were wide-ranging, including anthropology, history, geography, geology, medicine, law, religious studies, philosophy, painting, sculpture, theater, music, chemistry, physics, astronomy, poetry, technology, among others.[165][166] By the end of his reign, there were three libraries in São Cristóvão palace containing more than 60,000 volumes.[167] A passion for linguistics prompted him throughout his life to study new languages, and he was able to speak and write not only Portuguese but also Latin, French, German, English, Italian, Spanish, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, Sanskrit, Chinese, Occitan and Tupi-Guarani.[168][169][170][171][172] He became the first Brazilian photographer when he acquired a daguerreotype camera in March 1840.[173][174] He set up one laboratory in São Cristóvão devoted to photography and another to chemistry and physics. He also had an astronomical observatory constructed.[163]

The Emperor's erudition amazed Friedrich Nietzsche when both met.[175][132][176] Victor Hugo told him: "Sire, you are a great citizen, you are the grandson of Marcus Aurelius",[177][178] and Alexandre Herculano called him: "A Prince whom the general opinion holds as the foremost of his era because of his gifted mind, and due to the constant application of that gift to the sciences and culture."[159] He became a member of the Royal Society,[179] the Russian Academy of Sciences,[180] The Royal Academies for Science and the Arts of Belgium,[181] the American Geographical Society.[182] In 1875, he was elected to the French Academy of Sciences, an honor previously granted to only two other heads of state: Peter the Great and Napoleon Bonaparte.[183][178] Pedro II exchanged letters with scientists, philosophers, musicians and other intellectuals. Many of his correspondents became his friends, including Richard Wagner,[184] Louis Pasteur,[185] Louis Agassiz,[186] John Greenleaf Whittier,[187] Michel Eugène Chevreul,[188] Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,[189] Arthur de Gobineau,[190] Frédéric Mistral,[191] Alessandro Manzoni,[192] Alexandre Herculano,[193] Camilo Castelo Branco[194] and James Cooley Fletcher.[195]

Pedro II early realized that he had an opportunity to put the knowledge he was accumulating to practical use for Brazil's benefit.[196] The Emperor considered education to be of national importance and was himself a concrete example of the value of learning. [197][196] He remarked: "Were I not an Emperor, I would like to be a teacher. I do not know of a task more noble than to direct young minds and prepare the men of tomorrow."[198] Education also helped toward his goal to create a sense of Brazilian national identity.[199] His reign saw the creation of the Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute to promote research and preservation in the historical, geographical, cultural and social sciences.[199] The Imperial Academy of Music and National Opera[200] and the Pedro II School were also founded, the latter serving as a model for schools throughout Brazil.[201] The Imperial Academy of the Fine Arts, established by his father, received further strengthening and support.[202] Pedro II, with funds from his civil list, personally provided scholarships for Brazilian students to study at universities, art schools and conservatories of music in Europe.[197][203] He also financed the creation of the Institute Pasteur, helped underwrite the construction of Wagner's Bayreuth Festspielhaus, as well as subscribing to similar projects.[204] His efforts were recognized both at home and abroad. Charles Darwin said of him: "The Emperor does so much for science, that every scientific man is bound to show him the utmost respect".[132][205]

Popularity and clash with the British Empire

At the end of 1859, Pedro II departed on a trip to provinces north of the capital, visiting Espírito Santo, Bahia, Sergipe, Alagoas, Pernambuco and Paraíba. He returned in February 1860 after four months. The trip was a huge success, with the Emperor welcomed everywhere with warmth and joy.[206][207][208] The first half of the 1860s saw peace and prosperity in Brazil. Civil liberties had been maintained,[209][210] freedom of speech being one of the most important, having existed in Brazil since independence[211] and having been strongly defended by Pedro II.[212][213] The Emperor found newspapers from the capital and from the provinces an ideal way to keep track of public opinion and the nation's overall situation.[157]

Another means of monitoring the Empire was through direct contacts with his subjects. One opportunity for this was during regular Tuesday and Saturday public audiences, where anyone of any social class (including slaves[214]) could gain admittance and present their petitions and stories.[215][216] Visits to schools, colleges, prisons, exhibitions, factories, barracks, and other public appearances presented another opportunity to gather first-hand information.[217]

This tranquility disappeared when the British consul in Rio de Janeiro, William Dougal Christie, nearly sparked a war between his nation and Brazil. Christie, who believed in Gunboat diplomacy,[218] sent an ultimatum containing abusive demands arising out of two minor incidents at the end of 1861 and beginning of 1862. The first was the sinking of a commercial barque on the coast of Rio Grande do Sul after which its goods were pillaged by local inhabitants. The second was the arrest of drunken British officers who were causing a disturbance in the streets of Rio.[219][218][220] The Brazilian government refused to yield, and Christie issued orders for British warships to capture Brazilian merchant vessels as indemnity.[221][222][223] Brazil's Navy prepared for imminent conflict[224], purchase of coastal artillery was ordered,[225] several ironclads were authorized[226] and coastal defenses were given permission to fire upon any British warship that tried to capture Brazilian merchant ships.[227] Pedro II was the main reason for Brazil's resistance, he rejected any suggestion of yielding.[228][229][230][231] This response came as a surprise to Christie, who changed his tenor and proposed a peaceful settlement through international arbitration.[232][233][234] The Brazilian government presented its demands and, upon seeing the British government's position weaken, severed diplomatic ties with Britain in June 1863.[235][236][234]

War of the Triple Alliance

The first Fatherland Volunteer

As the threat of war with the British Empire became more real, Brazil had to turn its attention to its southern frontiers. Another civil war had begun in Uruguay turning its political parties against each other.[237][238][239] The internal conflict led to the murder of Brazilians and looting of their property in Uruguay.[240] Brazil's government decided to intervene, fearful of giving any impression of weakness in the face of conflict with the British.[241] A Brazilian army invaded Uruguay in December 1864 beginning the brief Uruguayan War, which ended on 20 February 1865.[242][243][244]

Meanwhile, in December 1864 the dictator of Paraguay, Francisco Solano López took advantage of the situation to establish his country as a regional power. The Paraguayan army invaded the Brazilian province of Mato Grosso (currently the state of Mato Grosso do Sul), triggering the War of the Triple Alliance. Four months later, Paraguayan troops invaded Argentine territory as a prelude to an attack upon the Brazilian province of Rio Grande do Sul.[245][242][246]

Aware of the anarchy in Rio Grande do Sul and the incapacity and incompetence of its military chiefs to resist the Paraguayan army, Pedro II decided to go to the front in person.[247] Both the Cabinet and the National Assembly refused to accede to the Emperor's wish.[247][248] After he also received objections from the Council of State, Pedro II made the memorable pronouncement: "If they can prevent me from going as an Emperor, they cannot prevent me from abdicating and going as a Fatherland Volunteer".[247][248][249][250] Thus those Brazilians who volunteered to go to war became known throughout the nation as the "Fatherland Volunteers" in homage to Pedro II's quote.[248] The monarch himself was popularly called the "Number-one volunteer."[251][132]

Pedro II left for the south in July 1865.[252][253][254] He disembarked in Rio Grande do Sul a few days later and proceeded from there by land.[255] The overland journey was made by horse and wagon, and at night the emperor slept in a campaign tent.[256] Pedro II arrived in Uruguaiana, a Brazilian town occupied by the Paraguayan army, on 11 September.[257] By the time of the Emperor's arrival, the Paraguayan force was besieged.[258][259]

The Emperor rode within rifle-shot of Uruguaiana to demonstrate his courage, but the Paraguayans did not attack him.[261][262] To avoid further bloodshed, he offered terms of surrender to the Paraguayan commander, which was accepted.[263][264][258] Pedro II's coordination of the military operations and his personal example played a decisive role in successfully repulsing the Paraguayan invasion of Brazilian territory.[265] There was a general belief that the war was near its end and that the surrender of López was imminent.[258][266][267] Before leaving Uruguaiana, he received the British ambassador Edward Thornton, who publicly apologized on behalf of Queen Victoria and the British Government for the crisis between the empires.[263][264] The emperor considered that this diplomatic victory over the most powerful nation of the world was sufficient and renewed friendly relations between the nations.[264] He returned to Rio de Janeiro and was received with huge celebrations.[268]

Conclusion of hostilities

Against all expectations, the war continued for almost five years. During this period, Pedro II's time and energy were devoted to prosecuting the war effort.[269][270] He tirelessly worked to raise and equip troops to reinforce the front lines, and to push forward the fitting of new warships for the navy.[250] At the same time, he worked to prevent quarrels between the national political parties from impairing the military response.[271][272] His refusal to accept any outcome short of total victory over the enemy was pivotal in the final outcome.[273][274] His tenacity was well-paid with the news that López had died in battle on 1 March 1870, bringing the war to a close.[275][276]

More than 50,000 Brazilian soldiers had died,[277] and war costs equalled eleven times the government's annual budget.[278] However, the country was so prosperous, that the government was able to retire the war debt in only ten years.[279][280] The conflict was a stimulus to national production and economic growth.[281] Pedro II turned down the National Assembly's suggestion to erect an equestrian statue of him to commemorate the victory and chose instead to use the money to build elementary schools.[282][283][284][285]

Apogee

An abolitionist in the throne

The diplomatic victory over the British Empire and the military victory over Uruguay in 1865, followed by a successful conclusion of the war with Paraguay in 1870, ushered in what is considered the "golden age" and apogee of the Brazilian Empire.[286] In a "general way, the 1870s were prosperous for the nation and its monarch. It was a period of social and political progress where the distribution of national wealth began to benefit a greater part of the population."[287] Brazil's international reputation skyrocketed and, with the exception of the United States, was unequalled by any other American nation.[286] The economy began undergoing rapid growth, and immigration flourished. Railroad, shipping and other modernization projects were adopted. "With slavery destined for extinction and other reforms projected, the prospects for 'moral and material advances' seemed vast."[288]

In 1870, few Brazilians opposed slavery and even fewer took an open stand against it. Pedro II was one of the few who did oppose slavery,[289][290] which he considered "a national shame."[291] The Emperor never owned slaves.[290] In 1823, slaves formed 29 percent of Brazil's population, but this figure had fallen to 15.2 percent by 1872.[292] The abolition of slavery was a delicate subject in Brazil. Slaves were used by everyone, from the richest to the poorest.[293][294] Pedro II wanted to end slavery gradually[260][295] to soften the impact to the national economy.[296] He consciously ignored the growing political damage to his image and to the monarchy in consequence of his support for abolition.[297]

The Emperor had no constitutional authority to directly intervene to put an end to slavery.[298] He would need to use all his skills to convince, influence and gather support among politicians to achieve his goal.[299] His first open move against slavery[291] occurred in 1850, when he threatened to abdicate unless the National Assembly declared the Atlantic slave trade illegal.[300]

After the overseas source for supplying new slaves had been eliminated, Pedro II turned his attention in the early 1860s to removing the remaining source: enslavement of children born to slaves.[301][302] Legislation was drafted at his initiative,[301] but the conflict with Paraguay delayed discussion of the proposal in the National Assembly.[303][302] Pedro II openly asked for the gradual eradication of slavery in the Speech from the Throne of 1867.[304] He was heavily criticized, and his move was condemned as "national suicide."[303][305][306] The charge was aired "that abolition was his personal desire and not that of the nation."[307] Eventually, the bill was enacted as the "Law of Free Birth" on 28 September 1871, under which all children born to slave women after that date were considered free-born.[308][309][307]

To Europe and North Africa

On 25 May 1871 Pedro II and his wife traveled to Europe.[310][311] He had long desired to vacation abroad. When news arrived that his younger daughter, the 23-year-old Lepoldina, had died in Vienna of typhoid fever on 7 February, he finally had a pressing reason to venture outside the Empire.[310][312][313] Upon arriving in Lisbon Portugal, he immediately went to the Janelas Verdes palace, where he met with his stepmother Amélie of Leuchtenberg. The two had not seen each other in forty years, and the meeting was emotional. Pedro II remarked in his journal: "I cried from happiness and also from sorrow seeing my Mother so affectionate toward me but so aged and so sick."[310][314][315]

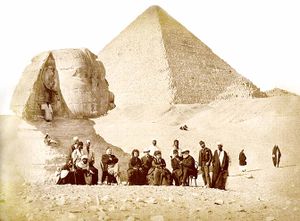

The Emperor proceeded to visit Spain, Great Britain, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Italy, Egypt, Greece, Switzerland and France. In Coburg he visited his daughter's tomb.[316][315] He found this to be "a time of release and freedom". He traveled under the assumed name "Dom Pedro de Alcântara", insisting upon being treated informally and staying only in hotels.[310][317] He spent his days sightseeing and conversing with scientists and other intellectuals with whom he shared interests.[310][315] The European sojourn proved to be a great success, and his demeanor and curiosity won respectful notices in the nations which he visited. The prestige of both Brazil and Pedro II were further enhanced during the tour when news came from Brazil that the Law of Free Birth, abolishing the last source of enslavement, had been ratified. The Imperial party returned to Brazil in triumph on 31 March 1872.[288]

Quarrel with bishops

Soon after returning to Brazil, Pedro II was faced with an unexpected crisis. The clergy had long been understaffed, undisciplined and poorly educated,[318][319] leading to a great loss of respect for the Catholic Church.[318] The Imperial government had embarked upon a program of reform to address these deficiencies.[318] As the Catholic Church was the state religion, the Emperor exercised a great deal of control over Church affairs,[318] paying clerical salaries, appointing parish priests, nominating bishops, ratifying papal bulls, and overseeing seminaries.[318][320] In pursuing reform, the government selected bishops which satisfied its criteria for education, support for reform and moral fitness.[318][319] However, as more capable men began to fill the clerical ranks, resentment of government control over the Church increased.[318][319]

The bishops of Olinda and Pará were two of the new generation of educated, zealous Brazilian clerics. They had been influenced by the Ultramontanism which spread in Catholicism in this period. In 1872 they ordered Freemasons expelled from lay brotherhoods.[321][322][323] Although European Masonry often tended towards atheism and anti-clericalism, things were much different in Brazil[324] where membership in Masonic orders was common.[325] The government tried on two separate occasions to persuade the bishops to repeal, but they refused. This led to them being tried before the Superior Court of Justice and convicted. In 1874, they were sentenced four years at hard labor, although the Emperor commuted this to imprisonment only.[326][327][328] Pedro II played a decisive role by unequivocally backing the government's actions.[329] [322][330]

Pedro II was a conscientious adherent of Catholicism, which he viewed as advancing important civilizing and civic values. While meticulously orthodox in matters of doctrine, he felt free to think and behave independently.[331] The Emperor accepted new ideas, such as Charles Darwin's Theory of Evolution, of which he remarked that "the laws that he [Darwin] has discovered glorify the Creator".[332] In sum, "clearly he was no fanatic."[333] What the Emperor could not accept was direspect to the civil law and government authority.[322][334] As he told his son-in-law: "[The government] has to ensure that the constitution is obeyed. In these proceedings there is no desire to protect masonry; but rather the goal of upholding the rights of the civilian power."[335] The crisis was resolved in September 1875 after the Emperor agreed to grant full amnesty to the bishops and annul their expulsion orders.[336][328] The main consequence of the crisis was that the clergy no longer saw any benefit in upholding Pedro II's throne.[322] Although they abandoned the Emperor, most eagerly awaited the accession of his eldest daughter and heir Isabel because of her ultramontane views.[337]

To the U.S., Europe and Mideast

Once again the Emperor traveled abroad, this time going to the United States. He was accompanied by his faithful servant Rafael, who had raised him from childhood.[338] Pedro II arrived in New York City on 15 April 1876, and set out from there to travel throughout the country; going as far as San Francisco in the west, New Orleans in the south, Washington, D.C., and even north to Toronto in Canada.[339][340][341] The trip was "an unnalloyed triumph", Pedro II making a deep impression on the American people with his simplicity and kindness.[342][343][182] He then crossed the Atlantic, where he visited Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Turkey, Greece, the Holy Land, Egypt, Italy, Austria, Germany, France, Britain, Netherlands, Switzerland and Portugal.[344][345] He returned to Brazil on 22 September 1877.[346]

Pedro II's trips abroad made a deep psychological impact. While traveling, he was largely freed of the restrictions imposed by his office.[347] Under the pseudonym "Pedro de Alcântara", he enjoyed moving about as an ordinary person, even taking a train journey alone with his wife. Only while touring abroad could the Emperor shake off the formal existence and demands of the life he knew in Brazil.[347] It became more difficult to reacclimate to his routine as head of state upon returning.[348] Upon his sons' early deaths, the Emperor's faith in the monarchy's future had evaporated. His trips abroad now made him resentful of the burden destiny had placed upon his shoulders when only a child of five. If he previously had no interest in securing the throne for the next generation, he now had no desire to keep it going during his own lifetime.[349]

Decline and fall

Decadence

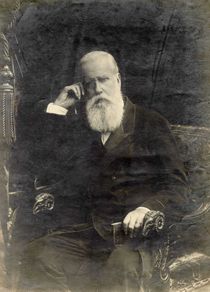

During the 1880s, Brazil continued to prosper and social diversity increased markedly, including the first organized push for women's rights.[350] On the other hand, letters written by Pedro II reveal a man grown world-weary with age and having an increasingly alienated and pessimistic outlook.[351][352] He remained respectful of his duty and was meticulous in performing the tasks demanded of the Imperial office, albeit often without enthusiasm.[352] Because of his increasing "indifference towards the fate of the regime"[353] and his lack of action in support of the Imperial system once it was challenged, historians have attributed the "prime, perhaps sole, responsibility" for the dissolution of the monarchy to the Emperor himself.[354]

After their experience of the perils and obstacles of government, the political figures who had arisen during the 1830s looked to the Emperor as providing a fundamental source of authority essential both for governing and for national survival.[62] These elder statesmen began to die off or retire from government until, by the 1880s, they had almost entirely been replaced by a younger generation of politicians who had no experience of the Regency and early years of Pedro II's reign, when external and internal dangers threatened the nation's existence. They had only known a stable administration and prosperity.[62] In sharp contrast those of the previous era, the young politicians saw no reason to uphold and defend the Imperial office as a unifying force beneficial to the nation.[355] Pedro II's role in achieving an era of national unity, stability and good government now went unremembered and unconsidered by the ruling elites. By his very success, "Pedro II had made himself redundant as emperor".[356]

The lack of an heir who could feasibly provide a new direction for the nation also diminished the long-term prospects for continuation of the Brazilian monarchy. The Emperor loved his daughter Isabel, but he considered the idea of a female successor as antithetical to the role required of Brazil's ruler. "Destiny had spoken in the loss of his two male heirs and the lack, after their death, of any more sons."[357] That view was also shared by the political establishment, who continued to harbor reservations when it came to any thought of accepting a female ruler.[358]

Republicanism was an elitist creed which never flourished in Brazil,[359][360] with little support in the provinces.[361][362][363] But a serious threat to the monarchy was the combination of republican ideas with the dissemination of Positivism among the army's lower and medium officer ranks, which led to indiscipline among the corps. They dreamed of a dictatorial republic which they believed would be superior to the liberal democractic monarchy.[364][365][364][366]

End of slavery and overthrown

The Emperor's health had considerably worsened[367] and his personal doctors suggested going to Europe for medical treatment.[368][369][370][371] He left on 30 June 1887.[368][371] While in Milan he passed two weeks between life and death, even being anointed.[371][372][373] While on bed recovering, on 22 May he received news that slavery had been abolished in Brazil.[374] Lying in bed with a weak voice and tears in his eyes, he said, "Great people! Great people!"[374][375][376][377] Pedro II returned to Brazil and disembarked in Rio de Janeiro on 22 August 1888.[378][379] The "whole country welcomed him with an enthusiasm never seen before. From the capital, from the provinces, from everywhere, arrived proofs of affection and veneration."[380] With the devotion expressed by Brazilians upon the return of the Emperor and the Empress from Europe, the monarchy seemed to enjoy unshakable support[381] and to be at the height of its popularity."[378][382][383]

The nation enjoyed great international prestige during the final years of the Empire[384] and it had become an emerging power within the international arena.[c] Predictions of economic and labor disruption caused by the abolition of slavery failed to materialize and the 1888 coffee harvest was successful.[385] The end of slavery had resulted in an explicit shift of support to republicanism by rich and powerful coffee farmers who held great political, economic and social power in the country,[386][387] since they regarded emancipation as confiscation of their personal property.[388] To avert a republican backlash, the government exploited the ready credit available to Brazil as a result of its prosperity. It made available massive loans at favorable interest rates to plantation owners and lavishly granted titles and lesser honors to curry favor with influential political figures who had become disaffected.[389] He also indirectly began to address the problem of the recalcitrant military by revitalizing the moribund National Guard, by then an entity which existed mostly only on paper.[390]

The measures made by the government alarmed the civilian republicans and the Positivists in the military corps. The republicans saw that it would undercut support for their own aims, and were emboldened to further action.[391] The reorganization of the National Guard was begun by the cabinet in August 1889, and the creation of a rival force caused the dissidents among the officer corps to consider desperate steps.[392] For both groups, republicans and military, it had become a case of "now or never".[393] Although there was no desire in Brazil among the majority of the population to change the form of government,[363] republicans began pressuring the Positivists officers to overthrow the monarchy.[394]

The Positivists launched a coup and instituted the republic on 15 November 1889.[395][396][397][398] The few people who witnessed what occurred did not realize that it was a rebellion.[399][400] "Rarely has a revolution been so minor."[401] During the whole ordeal Pedro II showed no emotion, as if unconcerned about the outcome.[402] He dismissed all suggestions for quelling the rebellion which politicians and military leaders put forward.[403][404][405][406] When he heard the news of his deposition he simply commented: "If it is so, it will be my retirement. I have worked too hard and I am tired. I will go rest then."[397] He and his family were sent to exile on 17 November.[407][408][409]

Exile and legacy

Last years

There was significant monarchist reaction after the fall of the empire, which was thoroughly repressed.[410] Riots in protest against the coup occurred, as well as pitched battles between monarchist Army troops and republican militias.[411] The "new regime suppressed with swift brutality and total disdain for civil liberties all attempts to launch a monarchist party or to publish monarchist newspapers."[412] Empress Teresa Cristina died a few days after their arrival in Europe[413][414] and Isabel and her family moved to another place while her father remained in Paris.[415][416] His last couple of years were lonely and melancholic, as he lived in modest hotels without money and writing in his journal of dreams in which he was allowed to return to Brazil.[417][418][419]

One day he took a long drive in an open carriage along the Seine, even though it was very cold. He felt ill after returning to the hotel that evening.[420][421] The illness progressed into pneumonia during the following days.[420][422] Pedro II rapidly declined and died at 00:35 a.m. on 5 December[423][424][425] surrounded by his family.[426] His last words were, "May God grant me these last wishes—peace and prosperity for Brazil..."[427] While the body was being prepared, a sealed package in the room was found, and next to it a message written by the Emperor himself: "It is soil from my country, I wish it to be placed in my coffin in case I die away from my fatherland."[424][428][429] The package, which contained earth from every Brazilian province, was duly placed inside the coffin.[428][430]

Princess Isabel wished to hold a discreet and private burial ceremony.[431] However, she eventually accepted the French Government's request for a State funeral.[432][433][424] On 9 December, thousands of mourners attended the ceremony at La Madeleine. Aside from Pedro II's family, these included: Amadeo, former king of Spain; Francis II, former king of the Two Sicilies; Isabella II, former queen of Spain; Philippe, comte de Paris; and other members of European royalty.[434][435] Also present were General Joseph Brugère, representing President Sadi Carnot; the presidents of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies[432] as well as their members; diplomats; and other representatives of the French government.[436] Nearly all members of the Institut de France were in attendance.[432][437] Other governments from the Americas and Europe also sent representatives, as did distant countries such as Ottoman Turkey, China, Japan and Persia.[436] Following the services, the coffin was taken in procession to the train station, whence it would travel to Portugal. Around 300,000[438] people lined the route despite incessant rain and cold temperatures.[439] The journey continued on to the Church of São Vicente de Fora near Lisbon, where the body of Pedro II was interred in the Braganza Pantheon on 12 December.[440][441]

The Brazilian republican government, "fearful of a backlash resulting from the death of the emperor," banned any official reaction.[442] Nevertheless, the Brazilian people were far from indifferent to Pedro II's demise, and "repercussions in Brazil were also immense, despite the government's effort to suppress. There were demonstrations of sorrow throughout the country: shuttered business activity, flags displayed at half-staff, black armbands on clothes, death knells, religious ceremonies."[440][443] Solemn "masses were held all over the country, which were followed by eulogies praising Dom Pedro II and the monarchy".[443]

Legacy

After his fall, Brazilians remained attached to the popular Emperor whom they regarded as a hero[444] and continued to perceive him as a national symbol, the Father of the People personified.[445] This view was even stronger among those of African descent, who equated the monarchy with freedom.[446] The phenomenon of continued support for the deposed monarch is largely credited to a generally held and unextinguished belief that he was a truly "wise, benevolent, austere and honest ruler."[447] The positive view towards Pedro II, and nostalgia for his reign, only grew as the nation quickly fell into a series of economic and political crises which Brazilians attributed to the Emperor's overthrow.[448] He never ceased being a popular hero, and would gradually become, once again, an official hero.[449]

Surprisingly strong feelings of guilt were manifested among republicans, and these became increasingly evident upon the Emperor's death in exile at the end of 1891.[450] They praised Pedro II, who was seen as a model of republican ideals,[451] and the imperial era, which they believed should be regarded as an example to be followed by the young republic.[452] In Brazil, the news of the Emperor's death "aroused a genuine sense of regret among those who, without sympathy for a restoration, acknowledged both the merits and the achievements of their deceased ruler."[453][444][454][447]

His remains, as well of his wife, were finally returned to Brazil in 1920 and the government granted Pedro II dignities befitting a Head of State.[455] A national holiday was declared and the return of the Emperor was celebrated throughout the nation.[451] Thousands attended the main ceremony in Rio de Janeiro. The "elderly people cried. Many knelt down. All clapped hands. There was no distinction between republicans and monarchists. They were all Brazilians."[456] This homage marked the reconciliation of Republican Brazil with its monarchical past.[457]

Historians have expressed high regard for Pedro II and his reign. The scholarly literature dealing with him is vast and, with the exception of the period immediately after his ouster, overwhelmingly positive, and even laudatory.[458] Emperor Pedro II is usually regarded by historians in Brazil as the greatest Brazilian.[1][8][9] In a manner quite similar to methods which had been used by republicans, historians point to the Emperor's virtues as an example to be followed, although none go so far as to advocate a restoration of the monarchy. "Most twentieth-century historians, moreover, have looked back on the period [of Pedro II's reign] nostalgically, using their descriptions of the Empire to criticize—sometimes subtly, sometimes not—Brazil's subsequent republican or dictatorial regimes."[459]

Titles and honors

| Styles of Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reference style | His Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

| Alternative style | Sire |

Titles and styles

- 2 December 1825 – 7 April 1831: His Imperial Highness The Prince Imperial

- 7 April 1831 – 15 November 1889: His Imperial Majesty The Emperor

The Emperor's full style and title were:

| “ | His Imperial Majesty Dom Pedro II, Constitutional Emperor and Perpetual Defender of Brazil.[460] | ” |

Honors

Emperor Pedro II was Grand Master (Sovereign) of the following Brazilian Orders:

- Order of Christ[461]

- Order of Saint Benedict of Aviz[461]

- Order of Saint James of the Sword[461]

- Order of the Southern Cross[461]

- Order of Pedro I[461]

- Order of the Rose[461]

He was a recipient of the following foreign honors:

- Grand Cross of the Austro-Hungarian Order of Saint Stephen.[462]

- Grand Cordon of the Belgian Order of Leopold.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Romanian Order of the Star.[462]

- Knight of the Danish Order of the Elephant.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Januarius of the Two Sicilies.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Ferdinand and of Merit of the Two Sicilies.[462]

- Grand Cross of the French Légion d'honneur.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Greek Order of the Redeemer.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Dutch Order of the Netherlands Lion.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Spanish Order of the Golden Fleece.[462]

- Stranger Knight of the British Order of the Garter.[463]

- Grand Cross of the Order of Malta.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Portuguese Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Portuguese Order of the Tower and Sword.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Prussian Order of the Black Eagle.[462]

- Grand Cross of all Russian orders of chivalry.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Italian Order of the Most Holy Annunciation.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Swedish Royal Order of the Seraphim.[462]

- Grand Cross of the Swedish Order of the Polar Star.[462]

- Grand Cross (First Class) of the Turkish Order of the Medjidie.[462]

Genealogy

Ancestry

The ancestry of Emperor Pedro II:[464]

| Ancestors of Pedro II of Brazil | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Issue

| Name | Portrait | Lifespan | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies (14 March 1822 – 28 December 1889; married by proxy in 30 May 1843[83][465][466]) | ||||

| Afonso, Prince Imperial of Brazil | 23 February 1845 – 11 June 1847 |

Prince Imperial of Brazil from 1845 to his death in 1847. He died in childhood. | ||

| Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil |  |

29 July 1846 – 14 November 1921 |

Princess Imperial of Brazil and Countess of Eu due to her marriage to Gaston d'Orléans. She had 3 sons from this marriage. She also acted as Regent of the Empire while her father was traveling abroad. | |

| Princess Leopoldina of Brazil |  |

13 July 1847 – 7 February 1871 |

Married Prince Ludwig August of Saxe-Coburg-Kohary with 4 sons resulting from this marriage. | |

| Pedro, Prince Imperial |  |

19 July 1848 – 9 January 1850 |

Prince Imperial of Brazil from 1848 to his death in 1850. He died in childhood. | |

See also

- Empire of Brazil

- Politics of the Empire of Brazil

Endnotes

- ^ "The Second Reign, that is, the period in which our Emperor was D. Pedro II, lasted fifty-eight years, from the abdication of his father, D. Pedro I, in 1831, until the proclamation of the republic in 1889." —Hélio Vianna[467]

- ^ "The peace was concluded and allowed, with the implementation of his ideals, the evolution of democracy in Brazil. There is not a more continuous period of tranquility in the history of South America, so different than the experiences of Brazil's neighbors [the South American republics formerly ruled by Spain] that J.B. Alberdi considered this the 'Brazilian miracle'. When the throne fell in 1889, Rojas Paúl, president of Venezuela, said, 'It has ended the only republic that existed in [South] America: the Empire of Brazil.' Mitre called it 'a crowned democracy'." —Pedro Calmon[468]

- ^ See Decline and fall of Pedro II for further details.

Bibliography

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Bueno (2003), p. 196.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 85.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Vainfas (2002), p. 198.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 4.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 45.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 424.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 503.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Vianna1994 (1994), p. 467.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Benevides (1979), p. 61.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Besouchet (1993), p. 39.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), pp. 11–12.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Olivieri (1999), p. 5.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 3.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 46.

- ↑ Besouchet (1993), p. 40.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Schwarcz (1998), p. 47.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 1.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 14.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Besouchet (1993), p. 41.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Calmon (1975), p. 5.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 15.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Carvalho (2007), p. 16.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Carvalho (2007), p. 13.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Olivieri (1999), p. 6.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 16.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 22.

- ↑ Besouchet (1993), p. 46.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 26.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 20.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Carvalho (2007), p. 21.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 15.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 17.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 50.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Carvalho (2007), p. 31.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 29.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Calmon (1975), p. 57.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 19.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Schwarcz (1998), p. 57.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 25.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 33.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Carvalho (2007), p. 27.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 8.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Vainfas (2002), p. 199.

- ↑ Besouchet (1993), p. 56.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 50.

- ↑ Besouchet (1993), p. 14.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 46.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 30.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 33.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Besouchet (1993), p. 50.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 9.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 33.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 29.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 39.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 21.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 53.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 37.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Schwarcz (1998), p. 67.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 11.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 67.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 38.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Barman (1999), p. 317.

- ↑ Bueno (2003), pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 10.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Barman (1999), p. 72.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 39.

- ↑ Bueno (2003), p. 195.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Schwarcz (1998), p. 68.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 136.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 70.

- ↑ Bueno (2003), p. 194.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 40.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 12.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 73.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 73.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 72.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 Barman (1999), p. 74.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 75.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 66.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 49.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 80.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 82.5 82.6 82.7 Barman (1999), p. 97.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 83.3 Carvalho (2007), p. 51.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 116.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 17.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 203.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 92.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), pp. 117–119.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 205.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 123.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 238.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 94.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 124.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 94.2 Calmon (1975), p. 239.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Schwarcz (1998), p. 95.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 96.2 96.3 96.4 96.5 Carvalho (2007), p. 52.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 240.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 98.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Barman (1999), p. 109.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Carvalho (2007), p. 9.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 81.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 187.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 Barman (1999), p. 122.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 111.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 114.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 123.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 124.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 111.2 Barman (1999), p. 125.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Barman (1999), p. 126.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Levine (1999), pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Skidmore (2003), p. 73.

- ↑ Bethel (1993), p. 76.

- ↑ Graham (1994), p. 71.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 118.2 Barman (1999), p. 159.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 100.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 162.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 164.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 163.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 165.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 167.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 178.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 120.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 170.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 73.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 127.

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 132.2 132.3 132.4 132.5 Vainfas (2002), p. 200.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 98.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 129.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 130.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 151.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 152.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 128.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 65.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 148.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 144.

- ↑ 144.0 144.1 Carvalho (2007), p. 80.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 134.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Skidmore (2003), p. 73.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 83.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 53.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 439.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 97.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 51.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 93.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 47.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 38.

- ↑ 157.0 157.1 Carvalho (2007), p. 79.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 326.

- ↑ 159.0 159.1 Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 104.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 77.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 116.

- ↑ Besouchet (1993), p. 59.

- ↑ 163.0 163.1 Barman (1999), p. 117.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 223.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 99.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 542.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 227.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 226.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 7.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 428.

- ↑ Besouchet (1993), p. 401.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 103.

- ↑ Vasquez (2003), p. 77.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 345.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 230.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 1389.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 258.

- ↑ 178.0 178.1 Carvalho (2007), p. 172.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 194.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 1787.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 94.

- ↑ 182.0 182.1 Barman (1999), p. 280.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 255.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 185.

- ↑ Lyra (v.3, 1977), p. 49.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 193.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 238.

- ↑ Lyra (v.3, 1977), p. 57.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 236.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 195.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 196.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 187.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 179.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 200.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 201.

- ↑ 196.0 196.1 Barman (1999), p. 118.

- ↑ 197.0 197.1 Barman (1999), p. 119.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), pp. 94–95.

- ↑ 199.0 199.1 Schwarcz (1998), p. 126.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p.152

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 144.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 99.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), pp. 226–228.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 182.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), pp. 200–207.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), pp. 138–141.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 188.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 200.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 192.

- ↑ Besouchet (1993), p. 515.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 84.

- ↑ Besouchet (1993), p. 508.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 27.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 180.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 94.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 184.

- ↑ 218.0 218.1 Calmon (1975), p. 678.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 207.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), pp. 103–145.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 208.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), pp. 678–681.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 104.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 680.

- ↑ Doratioto (2002), p. 98.

- ↑ Doratioto (2002), p. 203.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 684.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 191.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 28.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 209.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 685.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 210.

- ↑ 234.0 234.1 Carvalho (2007), p. 105.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 691.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 211.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 108.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 219.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 197.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 220.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 107.

- ↑ 242.0 242.1 Carvalho (2007), p. 109.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 198.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 299.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 227.

- ↑ 247.0 247.1 247.2 Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 228.

- ↑ 248.0 248.1 248.2 Calmon (1975), p. 734.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 32.

- ↑ 250.0 250.1 Barman (1999), p. 202.

- ↑ Schwarcz (1998), p. 300.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 229.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 735.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 111.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 736.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 112.

- ↑ Salles (2003), p. 52.

- ↑ 258.0 258.1 258.2 Carvalho (2007), p. 114.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 745.

- ↑ 260.0 260.1 Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 161.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 744.

- ↑ Pedrosa (2004), p. 199.

- ↑ 263.0 263.1 Calmon (1975), p. 748.

- ↑ 264.0 264.1 264.2 Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 237.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 205.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 239.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 725.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 750.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 193.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 110.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 219–224.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), pp. 116–118.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 206.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 229–230.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 121.

- ↑ Doratioto (2002), p. 461.

- ↑ Doratioto (2002), p. 462.

- ↑ Calmon (2002), p. 201.

- ↑ Munro (1942), p. 277.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 243.

- ↑ Calmon (1975), p. 855.

- ↑ Doratioto (2002), p. 455.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 122.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 230.

- ↑ 286.0 286.1 Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 9.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 37.

- ↑ 288.0 288.1 Barman (1999), p. 240.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 189.

- ↑ 290.0 290.1 Barman (1999), p. 194.

- ↑ 291.0 291.1 Olivieri (1999), p. 44.

- ↑ Vainfas (2002), p. 239.

- ↑ Olivieri (1999), p. 43.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 130.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 131.

- ↑ Lyra (v.3, 1977), p. 29.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 210.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), pp. 132–136.

- ↑ Lyra (v.1, 1977), p. 166.

- ↑ 301.0 301.1 Carvalho (2007), p. 132.

- ↑ 302.0 302.1 Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 162.

- ↑ 303.0 303.1 Schwarcz (1998), p. 315.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 134.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 133.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 164.

- ↑ 307.0 307.1 Carvalho (2007), p. 136.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 170.

- ↑ Barman (1999), p. 238.

- ↑ 310.0 310.1 310.2 310.3 310.4 Barman (1999), p. 236.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 175.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), pp. 172, 174.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), p. 180.

- ↑ 315.0 315.1 315.2 Carvalho (2007), p. 147.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 237–238.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), pp. 146–147.

- ↑ 318.0 318.1 318.2 318.3 318.4 318.5 318.6 Barman (1999), p. 254.

- ↑ 319.0 319.1 319.2 Carvalho (2007), p. 151.

- ↑ Carvalho (2007), p. 150.

- ↑ Barman (1999), pp. 255–256.

- ↑ 322.0 322.1 322.2 322.3 Carvalho (2007), p. 153.

- ↑ Lyra (v.2, 1977), pp. 205–206.